Applying to KAUST - Your Complete Guide for Masters & Ph.D. Programs (Upcoming Admissions)

Admissions Overview & Key Requirements

The New York Times reported Monday on findings released by Harvard's Classroom Social Compact Committee reveal that a growing number of students at the elite Ivy League school are skipping lectures, avoiding assigned readings, and shying away from challenging discussions—yet still managing to graduate with high honors.

According to Harvard’s undergraduate education dean, Amanda Claybaugh, the proportion of "A" grades awarded at the university has soared from 40% before the pandemic to 60% today. This disturbing trend, where "A" has become the most common mark, mirrors a broader national pattern: college GPAs rose more than 16% between 1990 and 2020, with top institutions like Harvard and Yale seeing "A" rates reach a staggering 79% in recent years.

Research suggests the primary drivers of grade inflation are, first, educators responding to “consumer demand” for higher grades from students, and second, students self-selecting into less rigorous courses and disciplines. Without question, sites like RateMyProfessor compound both drivers. Faculty members also worry about getting negative student evaluations if they are too tough in grading, the report says.

Harvard has long been trying to address its learning crisis. In Fall 2023, the university released a Report on Grading based on a May 2022 mandate to tackle grade compression. The initiative by Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) aimed to increase transparency and break the perverse incentives that encourage easy grading. To that end, the Office of Undergraduate Education (OUE) began a plan to provide departments with median grades (the middle grade) for all courses. This step publicly exposed departments whose average grades are excessively high, giving them the necessary data to drive internal discussions about raising academic standards. Additionally, the university mandated that departments should publish their specific grading approach and criteria on their websites to give students and other faculty clarity on the standards for marks like 'A' or 'B'.

Building on these efforts, Harvard expanded its reforms in 2024 to reshape the undergraduate learning experience. Professors were asked to take attendance and enforce device-free policies in classrooms, while students were encouraged to take notes by hand to reduce digital distractions. The university also added a new essay question to its admissions application, asking prospective students to describe a time they strongly disagreed with someone to promote open-mindedness and free exchange of ideas.

To tackle the "collective action problem" inherent in grade inflation, the policy experts, including Christopher Schorr, suggest large-scale, minimally burdensome solutions that focus on transparency.

The first one, initially proposed by Dr. Tom Lindsay, is to list the class average grade next to a student's grade on their transcript. This helps "lessen the perceived costs of rigorous grading" by validating a student who earns a B+ in a class with a B average over a student who earns an A- in a class with an A- average.

Another suggestion is to report the average standardized test scores (SAT/ACT) by course and department. This will allow universities to account for differences in "average student aptitude" when setting grading standards, ensuring that departments with genuinely high-performing students (like Biomedical Engineering) are not unfairly forced to lower their grades.

Share

Applying to KAUST - Your Complete Guide for Masters & Ph.D. Programs (Upcoming Admissions)

Admissions Overview & Key Requirements

Erasmus Mundus Joint Master's 2026 (Upcoming Admissions)

Erasmus Mundus programs are scholarships available to students worldwide, offering fully-funded Master’s degrees to study in Europe!

Registration Opens for SAF 2025: International STEAM Azerbaijan Festival Welcomes Global Youth

The International STEAM Azerbaijan Festival (SAF) has officially opened registration for its 2025 edition!

KAIST International Graduate Admissions Spring 2026 in Korea (Fully Funded)

Applications are open for KAIST International Admissions for Master’s, Master’s-PhD Integrated, Ph.D., and Finance MBA

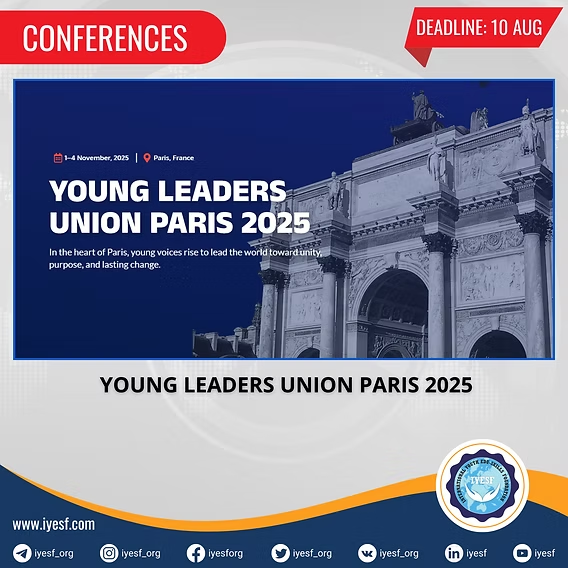

Young Leaders Union Conference 2025 in Paris (Fully Funded)

Join Global Changemakers in Paris! Fully Funded International Conference for Students, Professionals, and Social Leaders from All Nationalities and Fields

An mRNA cancer vaccine may offer long-term protection

A small clinical trial suggests the treatment could help keep pancreatic cancer from returning