Applying to KAUST - Your Complete Guide for Masters & Ph.D. Programs (Upcoming Admissions)

Admissions Overview & Key Requirements

In a significant shift in South Korea’s highly competitive education landscape, major national universities have begun denying admission to students based on their records of school bullying.

In the 2025 intake, a total of forty-five applicants across six key regional national universities saw their college dreams disqualified due to histories of school violence. This group included two students who were denied admission to the prestigious Seoul National University (SNU), despite of their high College Scholastic Ability Test (CSAT) scores.

Since the 2014 academic year, SNU has deducted up to two points from CSAT scores for applicants disciplined with transfers or expulsion. But the 2025 rejections mark the first known cases in which students were fully denied admission on these grounds.

The highest number of disqualifications came from Kyungpook National University, which turned away 22 students under its newly introduced point-based penalty system. Pusan National University followed with eight rejections, while Kangwon National University disqualified five students. Jeonbuk National University rejected five, Gyeongsang National University three, and Seoul National University two.

Four other national universities – Chonnam, Jeju, Chungnam and Chungbuk National Universities – did not reject any students on this basis, as they did not yet incorporate disciplinary penalties into their 2025 admissions process.

Beginning in 2026, however, all universities nationwide will be required to factor school violence records into evaluations.

The policy shift follows intense public debate sparked by revelations in 2023 involving former prosecutor Chung Sun-sin, who was briefly appointed head of the National Office of Investigation. It was later revealed that his son, who had been transferred for bullying a classmate, was admitted to SNU with only a minor two-point penalty. The backlash prompted the government to announce a mandatory nationwide policy by 2026, though many universities, including Kyungpook and Pusan, adopted the rules early.

School violence sanctions in Korea are categorized into nine levels — from a written apology, to restrictions on contact or retaliation, school or community service, mandatory education or counseling, suspension, class reassignment, school transfer and finally expulsion.

Until recently, lower-level infractions were often resolved through informal mediation between teachers, parents, and students. But under new guidelines, sanctions from Level 6 and above must be recorded permanently in the student’s official record.

Each institution determines independently how to weigh sanctions. Kyungpook National University applied deductions of 10 points for the lowest-level sanctions, 50 points for intermediate cases and 150 points for the most severe.

As a result, 11 applicants were rejected from the academic excellence, local talent and general admissions tracks; three from the essay-based admissions track; one from the agricultural entrepreneurship talent track; and four from performance and athletic talent tracks. An additional three applicants were denied in the regular admissions process.

Pusan National University implemented an even stricter approach, deducting up to 800 points from a 1,000-point scale for students with serious disciplinary records. Jeonbuk National University adopted a smaller but still consequential range, removing up to 50 points for expulsion cases.

Share

Applying to KAUST - Your Complete Guide for Masters & Ph.D. Programs (Upcoming Admissions)

Admissions Overview & Key Requirements

An mRNA cancer vaccine may offer long-term protection

A small clinical trial suggests the treatment could help keep pancreatic cancer from returning

Registration Opens for SAF 2025: International STEAM Azerbaijan Festival Welcomes Global Youth

The International STEAM Azerbaijan Festival (SAF) has officially opened registration for its 2025 edition!

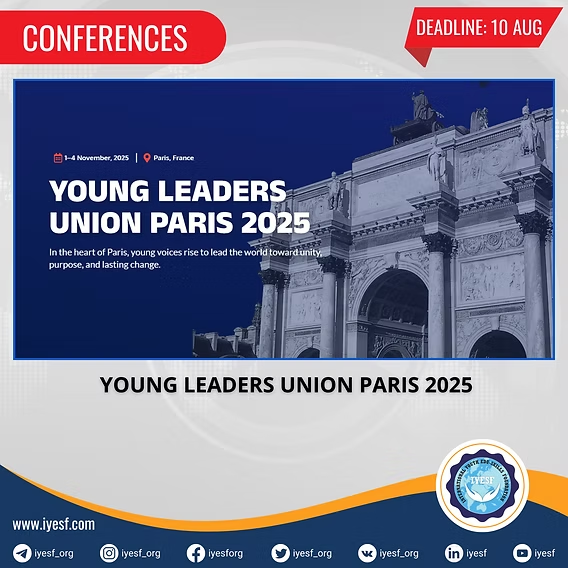

Young Leaders Union Conference 2025 in Paris (Fully Funded)

Join Global Changemakers in Paris! Fully Funded International Conference for Students, Professionals, and Social Leaders from All Nationalities and Fields

Yer yürəsinin daxili nüvəsində struktur dəyişiklikləri aşkar edilib

bu nəzəriyyənin doğru olmadığı məlum olub. Seismik dalğalar vasitəsilə aparılan tədqiqatda daxili nüvənin səthindəki dəyişikliklərə dair qeyri-adi məlumatlar əldə edilib.

Lester B Pearson Scholarship 2026 in Canada (Fully Funded)

Applications are now open for the Lester B Pearson Scholarship 2026 at the University of Toronto!